When I was working at Automated, a major project I designed and built from the ground up was an SMS interface for PerfectPlay - their IoT platform for managing sports field lighting systems.

This project was built for users and sites that are located in areas with poor cellular service.

Context

Conceptually, you can break the platform into 3 levels. Clients, Sites, and Fields.

Client:

- A client is generally something like a local council, a business, etc.

- A client can have many sites.

Site:

- Sites are generally locations separated by a some distance.

- They are generally areas such as a sporting precinct.

- Sites can have many fields.

Fields:

- A field is the lowest level, and is the physical area being lit.

- This is generally something like a cricket pitch, football field, etc.

A user can be given access to individual fields, individual sites (which also means access to all fields of that site), and individual clients (which means access to all sites of that client, and all fields of those sites).

Within PerfectPlay, there’s also the concept of a scene. A scene is a lighting preset for a given field. These are preconfigured arrangements of which lights to use, and the light level to use. Common configurations often have names such as “Match” (which would be all lights on at a high intensity, often for actual games of local sports teams), and “Training” (which, rather self explanatory, would be a lower level used when teams are just training).

Requirements for the SMS Interface

- Users must be able to authenticate themselves, and must be authorised to control the lights at the field they’re attempting to change.

- The SMS payload must be kept short and reasonably simple, as we want to minimise user input errors.

- Users should be able to request a list of valid scenes for a specific field.

- There should be plenty of clear feedback to the user, whether or not their request was valid, and whether or not it was successful.

Designing the Interface

Overview

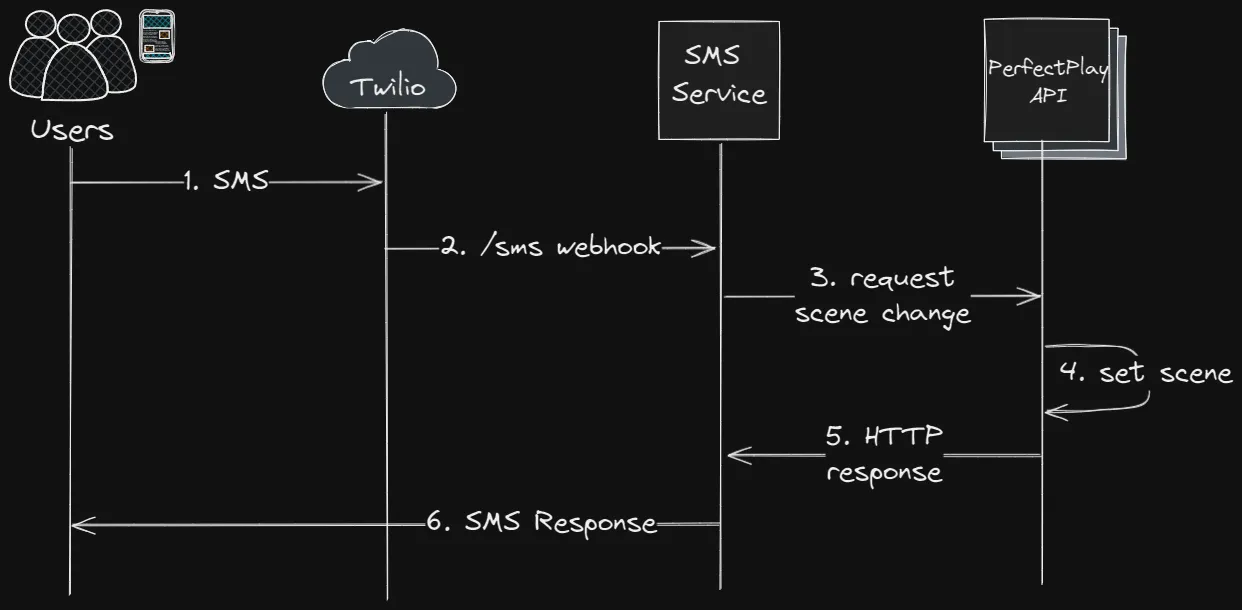

The SMS service was designed to be relatively quite simple. In short, all it had to do was receive an SMS, verify that the message matched the expected format, then make a request to the main sporting API, returning an SMS to the user depending on the HTTP response status code or if there were any internal errors processing the message.

The Payload

We started with the SMS payload. Internally, we were using UUIDs to identify unique clients, sites, and fields. We needed a way to target specific fields, but didn’t want users having to enter a UUID, so we decided on an abbreviation scheme. Fields often had generic names which may be repeated across many different sites (e.g. “Field 1”), so we couldn’t reasonably abbreviate a field and have it remain unique. Sites, however, were often unique enough that we decided an abbreviation of both a site and field name in conjunction would allow us to target specific fields. We also needed to specify what scene we wanted to change to. This was simply an integer.

We decided to use a delimiter to separate the abbreviations of the payload, and arbitrarily chose to use #.

At this point in time, given an example site “Example Grounds Sports Precinct”, and field “Football Field”, a reasonable payload could look like:

EGSP#FBF#2

Where EGSP is the abbreviated site name, FBF is the abbreviated field name, and 2 is the scene we’d like to set it to.

Authentication

Now, we didn’t want just anyone being able to send a text to control the lights. So, we opted to allow users to verify through 2 methods.

The first was simply to add a PIN number to the payload.

A reasonable payload could now look like:

ABC123#EGSP#FBF#2

Where ABC123 is a users PIN.

The second method was to allow users to associate their phone number to their account, verifying it with a one time passcode. Any messages coming from this phone were then implicitly authenticated.

An edge case: Some clients preferred to simply use one ‘master’ account to access the platform, and would give the credentials to many different people. For this reason, the PIN number takes precedence over the implicit authentication, as it was a possibility that a user’s number wouldn’t be associated to a field they were granted access to.

Implementing the SMS Service

The service was written in Go, and deployed to Google Kubernetes Engine.

Integrating with Twilio

To receive SMS messages, we integrated with Twilio. The way we set this up was that we paid for a phone number from Twilio, and configured that number to forward any messages to our service using a webhook.

Twilio Validation

To validate that a request came from Twilio, they include a signature in the X-Twilio-Signature request header. Our service had to hash the full request URL, request params and our Twilio Auth Token, and compare that with the provided signature. If the hashes matched, we could continue with processing the request.